Donald W. Winnicott, psychoanalyst of the British Object Relations School, is one of my intellectual heroes. His theories on how our early childhood development shapes our later relationships and creative work are fascinating.

In “Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena” (published in the “International Journal of Psycho-Analysis” and his “Collected Papers,” 1953 and 1958, respectively), he argues that the special possessions very young infants grow attached to—such as a doll, teddy bear or blanket—are transitional objects to help them distinguish external reality (or the “not me”) from their own “subjective omnipotence”—i.e., the belief that their wish for an object creates the object. Watching this clip of Big Bird, I think of another one of Winnicott’s observations on the relationship with the transitional, which is that the object must never change, unless it is changed by the infant. Here Big Bird is like an infant involved in doing and undoing, showing omnipotence of a sort:

from their own “subjective omnipotence”—i.e., the belief that their wish for an object creates the object. Watching this clip of Big Bird, I think of another one of Winnicott’s observations on the relationship with the transitional, which is that the object must never change, unless it is changed by the infant. Here Big Bird is like an infant involved in doing and undoing, showing omnipotence of a sort:

Whenever I watched the television series “The Polka-Dot Door” I was on the alert for the rare visits made by another large, seemingly friendly creature, the Polkaroo. Transitionality is readily apparent in the clip below, Polkaroo quietly and stealthily sallies onto the set, but then disappears as quickly, like a slight breeze on a hot day or the flirtatious flits of a seasonal butterfly. It’s a different kind of transitional, one that reminds me of the presence and absence of a mother figure.

TVO, “The Polka-Dot Door: The Polkaroo Was Here” (1981)

Both of the show’s hosts are dismayed and a bit surprised by the Polkaroo’s coming and going, though the man’s saying he missed him again suggests that it is a recurrent fact of life, or perhaps an acknowledgment that imaginary friends do exist, even if adults keep missing them.

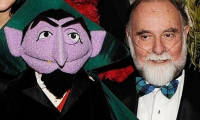

Big Bird’s imaginary friend, Mr. Snuffleupagus, only made an appearance on the street in the seventeenth season. Until then, nobody believed the mammoth existed—he was considered a figment of Big Bird’s imagination, always fleeing the scene much like Polkaroo.

In the clip below, Big Bird and Mr. Snuffleupagus go to Hawaii in search of what I think must be a maternal figure, a certain Snuffleupagus Mountain (15:25). As the scene opens, they have looked far and wide, and feel a bit tired of the search. Mr. Snuffleupagus receives a phone call from his mother, and although Big Bird expresses what a wonderful thing this is, Snuffy remains weary. Then Snuffy wishes he was back in his cave with his “Mommy” to take care of him. The absence of the mother is even felt in her voice, in her belabored motherly advice.

Sesame Street, “Hawaii Day 3: Big Bird and Snuffy search for the Snuffleupagus Mountain” (Ep. 1092, 1978)

A final pathetic fallacy: As Mr. Snuffleupagus is given assurances that Big Bird will continue the search for the mountain, we catch sight of it in the background. Snuffy settles down for a nap.

Snuffy’s external reality is not fully realized. Big Bird is his best transitional object.

– Nyla Matuk