Nitro, “Freight Train,” (“O.F.R.” [“Out-Fucking-Rageous”] 1989)

How did we get from Roy Acuff’s “Wreck of the Old 97” to Aerosmith’s “Train Kept a Rollin’” to Nitro’s “Freight Train”?

Trains used to chug along, conductors “high on cocaine,” but still choo-chooing on their mazy way, until Nitro. Nitro confronts us with something altogether different. It’s as though we drifted off on yesterday’s rock rhythms only to bolt awake on the tracks blinded by the lights of an oncoming express. All senses are overwhelmed, and then, before you know it, you’re gone. Whatever else this is, it is no longer rock music.

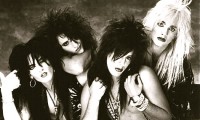

Nitro is a band (not a rollercoaster or wrestler) almost entirely defined by, and remembered for, gimmicks. The band boasted at least two musicians with super-powers: The lead singer Jim Gillette (Lita Ford’s husband) claimed the ability to break glasses with his voice like an opera soprano of old, and guitarist Michael Angelo Batio was allegedly the “fastest” guitarist in the world (the bass player’s powers seem to consist of his ability to swing his bass in a circle like a Weight-Throw contestant in the Highland Games; the drummer may be merely human).

While musical speed and range, displayed as sublime virtuosity, can have a pleasing, even dizzying effect when it issues from the piano of an Art Tatum or the strings of a Paganini, musical quality is not generally measured in notes-per-second. Certainly scale and intensity lend themselves to what we think of as “greatness,” but they do not work alone and they cannot work without context. There must be something to rise up from. You can’t begin on eleven.

In Nitro the listener is met with a warlike barrage of genuinely irritating sonic gymnastics. For all his alleged range (six octaves claimed, but four octaves according to critics), Gillette makes one wish he came equipped with a mute button. (One may also feel the distinct urge to pull his wig off.)

Batio’s playing is shrill, antagonistic, and ultimately unnecessary. In fact, it is not merely unnecessary, or unnecessarily busy; it is, in fact, insanely busy, existing for the very sake of busyness. If an obsessive-compulsive sewing machine could play music, this is what it would sound like. Batio never once smiles or seems to enjoy himself. Gillette seems to plead anxiously the entire time, on the verge of some sort of calamitous breakdown. Do we not understand? He is like a freight train coming. Get it?

This is art as competition. Art as exaggeration. Every convention of rock music is overstated or embroidered to cartoonish degrees. This goes for their equipment as well. We all remember the classic double-necked guitar (twelve and six strings) employed to great effect by Jimmy Page in his performance of Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” from the concert film “The Song Remains the Same.”

Then we had the grinning trickster Rick Nielsen, guitarist for arena-pleasers Cheap Trick, who pushed this innovation to an absurd end with his five-necked Hamer custom guitar. What good are five identical six-string necks? Who cares? That’s Nielsen’s point.

Rick Nielsen performs on his five-necked custom guitar (“Cheap Trick Live In Chicago”)

Then we get the straight-faced Batio’s famous “quad guitar,” which provides him with the implausible and perfectly pointless ability to play four different six-stringed necks at different times, two in mirror opposition to his normal configuration (named second “coolest guitar in rock” by online music magazine Gigwise; Rick Nielsen’s penta-guitar came in fifth, Page’s first).

Acrobatic? Yes. Impressive? Kinda. Pleasing to the ear? Never.

Nitro, “Freight Train” quad-guitar solo highlight (1989)

Nothing can mask the fact that “Freight Train” is not a good song. The video’s director generously interlards footage of the band bopping and pouting around a sound stage with stock footage of a train. Yes, that’s right, an actual train, steam and all.

The director for Soul Asylum’s “Runaway Train” saved a goofy song from becoming goofier by showing photographs of missing children in the MTV video. This tactic made an otherwise forgettable song heartbreaking. But neither Nitro nor the director they retained for the video shoot are remotely concerned with subtlety. Even seasoned metal listeners will wince at least once during Batio’s front-loaded, claws-out guitar solo.

We must remember that “Freight Train” was released during the apocalyptic apex of “shred” guitar, when more and more guitarists battled for an ever shrinking share of the music entertainment market. Competition was severe.

Indeed, Batio was named “No. 1 Shredder of All Time” by Guitar One Magazine (how many of these magazine are there?) as late as 2003 (not best guitarist). Tricks of all kinds were in, like never before, or since. You could play the guitar upside-down, backwards, while spinning it around your spandexed torso; shoot rockets from it, blow it up, ignite the pickups, shoot lasers from the pegboard, anything, everything! Speed, more speed! If it’s too late to be the loudest band in the world, never fear: There is still time to be the fastest.

Guitarists became daredevils, pushing themselves and their gear to limits never heard before (and which no one wants to hear again!). Paul Gilbert, guitar prodigy, became known for actually playing solos using a modified drill bit with three picks attached, like blades of a propeller, to pluck the notes at baffling speed. He was that fast.

masterguitarforro, “Guitar prodigy Paul Gilbert Plays Drill Guitar”

Much of the blame for this trend in rock music—the trend that reached its illogical conclusion with Nitro—may be laid at the doorstep of one David Lee Roth. As front man for the biggest rock show on earth, Van Halen, he was compelled to stage an even bigger show upon his departure for a solo career.

David Lee Roth hams it up on “Just a Gigolo” (“Crazy from the Heat” 1985)

He was always the most vaudevillian of rock stars, and in his cosmopolitan, silver-tongued way he resembles stars like Bob Hope or Dean Martin more than primordial, mystical rockers like Jimi Hendrix or Robert Plant (he announced this at the start of his solo career by the decision to release this Frank Sinatra-esque version of an old Irving Caesar standard). He was a showman par excellence. Roth’s was a theatrical, wise-assed, variety-style of entertainment, far from the booming sludge of Black Sabbath, the druggy ease of The Eagles, or the psychedelic escapism of Pink Floyd. The man believed in ballyhoo.

“Diamond” Dave, “Yankee Rose” (“Eat ’em and Smile,” 1986)

In his bid to outdo all comers, Roth hired the two most impressive (because excessive) performers of their kind: Steve Vai (guitar) and Billy Sheehan (bass). This lineup, and the incredibly lucrative tour that ensued, inspired an orgiastic enthusiasm for speed and flair on the part of hard rock musicians everywhere, who entered into a mutually-destructive arms race that peaked at the end of the decade, when such peacock performances would be made obsolete by morose, shoe-gazing rock produced by ironic and depressive Grunge artists.

After the hair-sprayed minstrelsy, musical burlesque, and outright freak shows of heavy metal, both kids and critics felt that Seattle represented a refreshing, refining return to the “authenticity” that had been bled out of rock music over the previous ten years by Los Angeles.

But let us return to Nitro, shall we?

It is instructive to note that both lead members offered lessons — “Vocal Power” and “Speed Kills” — by mail through a system called “Metal Method,” advertised in rock magazines like Circus and Hit Parader. What they did was, at root, aspirational (Batio pauses in his instructional video to promise “I’m going to give you the keys to the Lamborghini”).

Michael Angelo Batio in his “Speed Kills” course for “Metal Method” (1984)

Who wouldn’t want to get better, especially if they could be the best . . . ever, in history! Nitro’s exploits resembled athletic performances (or professional wrestling moves) more than musical expression. No “slow hand” for these LA rockers.

Watch Batio: A guitar lick easily played with a small movement of a single finger is instead frantically performed with a great lashing about. Showmanship, not musicianship.

They may have thought they embodied the future, but they really were just the latest in a lemming dash over the cliff of rock history. In fact, if you listen, you realize they shed the chrysalis of blues music from which rock had been born altogether, though in their desperate reach for some kind of Baroque post-rock transcendence they instead fell like Evel Knievel right down into the yawning canyon of their own vaunting ambition.

Before the 80s are done, heavy metal gets even crazier, and lazier.

– Ernest Hilbert